Reflective Summary – G.Bailey – Production of ‘George’

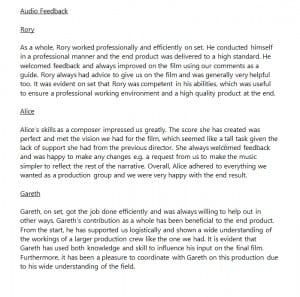

The image above documents the positive email feedback we received on my group’s involvement with the production team during the production of George, which speaks directly to the achievement in my first learning outcome for the project pertaining to the role of Supervising Sound Editor – To successfully manage the audio team’s interaction with film’s director, editor and producer on a practical and creative level, and ensure the audio team’s work is delivered on time and to a good standard – and one of my personal learning outcomes – To successfully manage a three person team in delivery of the entire soundtrack to a new piece of visual media efficiently.

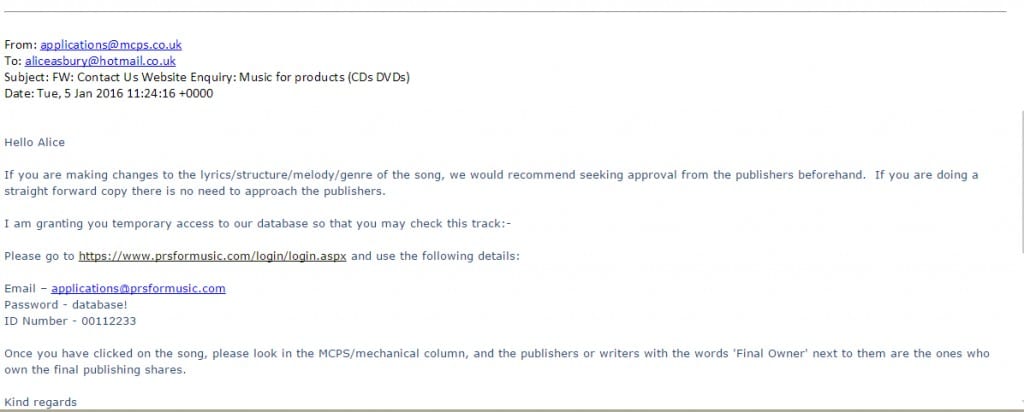

Interaction with the client was one of the most critical parts of the process from my perspective as well as the most fraught, due to the two seperate directorial directions the film required and the production problems around the time of the original directors departure. The fact that we delivered audio for the film under complicated circumstances which met and exceeded the client’s expectations in some areas on time and on target (with respect to the extension granted us) whilst having had to guide the direction of the audio for the film with little collaborative support from the creative lead in it’s early stages, and still received universally positive feedback suggests I successfully managed the interactions with the relevant personnel. I dealt with a great number of logistical and technical problems for both the media groups involved throughout the production, generally made the final call on decisions about our priorities when I was able to do so, spent a great deal of time trying to keep spirits up on all sides as problems mounted, and attempted to encourage the other members of the audio team to look at things I felt they were perhaps missing (like trying to clear the director’s music choices via PRS, rather than taking an easy, copyright free, option). In managing the process here, I learnt above all that I should be more expectant of the kind of problems thrown up throughout because, whilst I classed them initially as unusual difficulties, according to the industry sources I consulted they appear par for the course in film production.

To judge the initial direction of and maintain the consistency of the overall tone of the audio team’s work on the piece, and liase with the director to ensure this is concurrent with their vision of the piece – This outcome is more difficult to judge because the initial direction of the audio for the piece was not necessarily the direction that was requested of our work after Christmas, which is not to say I misjudged either directors requirements as far as I’m aware, and no one aspect of the audio particularly jars with any other. There are plenty of tangible examples that stemmed from the requests of the two creative leads – audio devices influenced by Green Mile, the use of the specific radio track at the behest of the second director etc – in the final artifact that will testify to the attention to directorial requirements paid throughout both the pre production and production process. Of scenes in which I led the sound design, I feel we did everything we possibly could to bolster the story without overstepping the boundaries created by the picture, even though this was fairly frustrating as we could clearly see the initially strong idea being buried under the production problems, and I consistently pushed for the audio dimension to be given as much headway as possible to help tell George’s story, even as the picture was hampered in doing so. This approach was also, ultimately, in keeping with both director’s vision for the piece.

To manage the post-production workflow and contribute substantially to the sound design, construction and editing of the piece – Getting down to the nuts and bolts of the post-work aspect of the Supervising Sound Editor’s role, I can cite my overall contribution as evidence of my success here. I put a lot of time and effort (at least 60 hours of editing and foley work alone) into making a slightly confused final edit as good as it could audibly be across the various disciplines of audio post-production work, as well as dealing with much of the final quality-control decision making and the crucial final mix and master stage, all under considerable time pressure and with sometimes weekly changes to client requirements. The detail of some of the managerial and technical challenges are documented elsewhere in this blog, though it is worth mentioning the main one from an editing perspective was the lack of information forthcoming about changes from the films editor until we pressed home this information’s importance, and both my team and the client are apparently proud of or happy with the technical aspects of ‘George’ I’ve had a hand in. I also feel this level of involvement in the film satisfies my personal intention to have a good degree of creative involvement in the conception and direction of the soundtrack for the piece. There are plenty of ideas and work I can call my own in the audio of this film.

To manage the delivery of the soundtrack at various stages of the production along with relevant paperwork, to the director and producer – The various deadlines for all the groups have been met consistently throughout the process, and all paperwork completed as per the supporting materials of this blog.

Moving on to personal learning outcomes not particularly related to my official ‘role’ within the production I will say only a few words as I would hope they are self-evidently fulfilled by information furnished elsewhere in this blog –

To expand my knowledge of the theory and audio techniques deployed in the films influencing ‘George’, and in drama as a genre more generally – I refer to my research posts here, and ven though I at first thought the big budget reference points that were furnished to me for the films sound design would be difficult to find relevant material in, I was surprised at the amount of useful information I was able to glean from them through researching their creators.

To contribute extensively to the practicalities of creating and recording music for, and of recording location sound for the piece – This outcome encompasses my only real regret about the production in that I simply could not find the time to get involved in the composition of the music as I would have liked to. This is not to detract from the music in practical terms nor to say I didn’t have a hand in okaying the direction of the original compositions alongside my contribution to recording and mixing them, merely to say that as far my fairly ambitious outcomes are concerned this one was a bridge too far. As I more than fulfilled this requirement in terms of my first experience of location audio work and learnt a great deal from my colleagues in that matter, 50% will have to be enough here.

Conclusion – critical appraisal of the film as a finished piece:

Group Aim

- To create and deliver the soundtrack to the film ‘George’ by Lucy Norton, Charlotte Hughes, Shaun Standring and Angelin Selvanathan.

Group Objectives:

- To create an effective musical score and soundtrack that suits the themes of the film and supports the story in a manner concordant with the picture and the preferences of the director.

- To successfully manage and conduct location recording to capture useful dialogue and atmospheres that will form the basis for some sound design aspects of the picture.

- To create believable and relevant atmospheres and sound effects in post-production, and edit these into a full soundtrack using foley, location recordings, composed music and replaced dialogue where applicable.

- To final mix the project and deliver it at a good standard.

Watching ‘George’ with a critical eye I cannot find an area where we have spectacularly missed the mark on any of the above objectives and we certainly fulfilled our main aim. I would make the following observations however –

Dialogue is intended to tell ‘the human story’ of the film, and the revised script’s lack of it is severely problematic in a film intended to tell one man’s story. My feeling is it fell to the music in George to attempt to make up for this lack of emotion, and as such I would have liked to have been able to increase the complexity of our compositions and recording techniques to make this more effective. This was an opportunity to prioritise composition we arguably missed in the early stages, though without picture to compose to it would have been very hard to do.

We found ourselves in the dreaded position of having committed detailed audio work to picture only to have the editor change the cut. I knew this wasn’t desirable as a method of working, but the pressure to get SOMETHING underway in the audio realm as the production lost coherence and fell further and further behind was overwhelming. This introduced a huge degree of inefficiency, necessitating spending some hours resyncing scenes, but was necessary in order to avoid having to condense the entirety of a month’s worth of work into a short period in January after picture lock was completed.

The axing of various complex audio ‘show-stopper’ scenes explains the ‘peaks and troughs’ of the audio dimension to my mind. Our more abstract sound plans were not always built upon similarly complex and layered foundations, and I think this means the sound in George is often found leading the image, but elsewhere feels somewhat strait-jacketed by the image as we were forced to use more ‘parallel sound’ than we would have liked by the picture. One could argue it’s a little inconsistent dynamically in this sense, and this will teach me to pay more attention to the core aspects of film atmosphere’s rather than getting carried away with the areas in which the team could show off.

In conclusion, production of George was a great learning experience and worked as an opportunity to really get into coordinating the audio side of a film production and problem-solving the inevitable issues, as well as providing ample opportunity for plenty of nuts and bolts audio production work. However, after making it the focus of our daily lives for almost four months, I can honestly say I’ll be happy if I never have to hear George weeping again and that I’m looking forward to seeing parts of the university which aren’t the Sound Theatre once more too.

– 1749 words